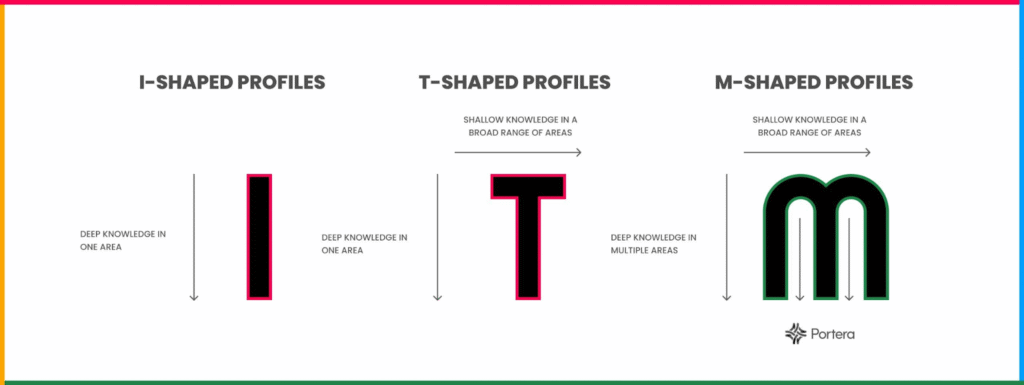

Every major technological revolution reshapes not only the tools we use but the skills we need. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, most people lived and worked within small, self-contained economies such as farms and workshops. Their skillsets were deep and narrow, specifically honed for mastery within a single craft or trade – think the cobbler, or the seamstresses. With industrialisation, came mechanisation, and mass production. This demanded a new kind of worker: one capable of coordinating across machines, departments, and processes. The “I-shaped” worker, with expertise in one domain, evolved into the “T-shaped” worker; someone with deep knowledge in one area but broad understanding across several.

Now, with artificial intelligence, automation, and the fusion of physical and digital economies, we are standing at the precipice of another transformation. The emerging model of the future may be best described as “M-shaped”: workers who hold deep specialisation across multiple domains. The fundamental difference here is that the new worker needs to be adaptable, emotionally intelligent, and well adjusted to lifelong learning. Before turning to the central discussion of what this transformation means for the next generation of workers, educators, and employers, it’s important to first establish meaningful context by examining the historical transitions that brought us here.

The Pre-Industrial Era: The Age of I-Shaped Mastery

Before the Industrial Revolution, work was largely local, seasonal, and skill-intensive. The majority of people were engaged in agriculture or artisanal craftsmanship. A farmer knew how to read the soil, the weather, and care for animals. A blacksmith understood metal and how to shape it. A weaver knew about dyes, patterns, and textures. These skills were learned through doing, often taught by parents or mentors, not in a classroom. Trades were usually passed down from one generation to the next, so the skills of a parent often became the child’s future too (Epstein, 1998).

In these examples, skillsets were “I-shaped”: vertical, specialised, and rarely transferable. A cobbler could not easily become a carpenter; their worlds of knowledge were separate and siloed.

Work rhythms were dictated by nature and community, not machinery or time clocks. The goal was sustainability rather than productivity. This period produced masters of craft but not necessarily innovators or collaborators in the modern sense (Mokyr, 1990).

The Industrial Era: The Birth of T-Shaped Worker

The Industrial Revolution (roughly 1760–1840) fundamentally altered economic structure and human labour (Britannica, n.d.; Britannica, “Industrial Revolution” 2025). Handcraft production gave way to mechanised factories. Workers acquired new and distinctive skills, and their relationship with their tasks shifted; instead of working with hand tools, many became machine operators in factories (Britannica, n.d.; Encyclopedia Britannica, “Industrial Revolution” 2025).

In this era, skill was redefined. Workers needed functional understanding across several areas, including operating machines, managing schedules, and coordinating tasks, even if they no longer possessed the deep artisanal knowledge of their predecessors. The new “T-shaped” worker had both:

- Depth: Specialisation in one functional area, such as operating a loom or managing inventory.

- Breadth: Awareness of related systems and processes that enabled them to function within an industrial ecosystem.

As economies industrialised, educational systems had to evolve to produce workers with general foundational knowledge (reading, writing, numeracy) that could be applied across different settings (Howes, 2017). The innovators of the Industrial Revolution often had interdisciplinary backgrounds, combining technical, managerial, and organisational knowledge (Howes, 2017). Take Thomas Edison, for example, who wasn’t only an inventor. He combined his understanding of science and engineering with sharp business and leadership skills, building one of the first global research labs, coordinating teams of skilled workers, and transforming ideas into products that could be mass-produced and sold. This kind of interdisciplinary skill set became increasingly valuable in a fast-changing economy.

The Social Cost of Mechanisation

While the Industrial Revolution improved efficiency, it also fragmented labour. Many traditional crafts disappeared. The rise of the factory discipline reduced autonomy, replacing creative mastery with repetitive precision. Movements like the Luddites reflected the anxiety of workers whose deep craft expertise was suddenly obsolete.

However, industrialisation also laid the groundwork for interdisciplinary collaboration. Engineers, chemists, and managers had to blend technical and organisational knowledge — the earliest version of “T-shaped” skillsets that combined specialisation with cross-functional understanding.

The Digital Era: The Rise of the Knowledge Worker

By the mid-20th century, technology, more specifically the internet, transformed work. The knowledge economy of the late 1900s and early 2000s valued not only what workers could do but what they could know. Computers, global markets, and data required workers to navigate increasingly complex information systems.

This era saw the formalisation of the T-shaped skills model, popularised by organisations like ibm and McKinsey. Employees needed both:

- Deep technical or professional expertise (the vertical of the “T”), and

- Broad competencies such as communication, creativity, and collaboration (the horizontal bar).

This model became the foundation of higher education and workforce training in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The objective, to prepare workers for jobs that demanded both analytical depth and interpersonal skills.

What’s the Next Revolution? The M-Shaped Worker.

We are now entering an era where even T-shaped skills are no longer enough. Artificial Intelligence, automation, robotics, and biotechnology are creating a world where the boundaries between domains are blurring more than ever before. For example:

- A data scientist who is also fluent in behavioural psychology and storytelling.

- A healthcare professional with deep knowledge in both clinical practice and digital analytics.

- An engineer who can lead teams, understand user experience, and apply AI ethically.

Why This Shift Is Inevitable

Three forces are driving this new profile:

- Automation of Routine Work:

Repetitive, predictable tasks (once the bread and butter of industrial labour) are increasingly automated. Human value now lies in non-routine cognition and interdisciplinary creativity. - Convergence of Disciplines:

Fields such as AI, biology, and design are merging, requiring workers who can integrate knowledge across boundaries. - Career Fluidity and Lifelong Learning:

Future careers will be nonlinear. Workers will pivot multiple times, building stacked specialisations rather than a single lifelong trade.

The Educational and Cultural Implications

Education must pivot from producing narrow specialists to cultivating adaptive polymaths. This doesn’t mean returning to Renaissance-style generalism; rather, it means fostering multiple deep competencies supported by the ability to learn, unlearn, and reapply knowledge across contexts.

Corporations, too, will need to redesign training and talent models — valuing learning agility and cross-domain collaboration over rigid job titles. Lifelong learning platforms, micro-credentials, and AI-driven skill mapping will become core to employability.

The Human Skills That Endure

As machines become capable of increasingly complex analysis, human value shifts toward what is hardest to automate:

- Empathy and communication

- Critical and ethical reasoning

- Creativity and synthesis

- Collaboration and cultural intelligence

In the M-shaped paradigm, technical depth is necessary but just not enough. The new premium is on meta-skills: the ability to learn fast, adapt often, and connect ideas creatively. These skills become the connective tissue between multiple areas of deep expertise.

So what does that mean for the Future Workforce?

In so many words… Pivot, Layer, Connect. The 21st-century career is highly unlikely to be a ladder, but a lattice built through several pivots and projects. Workers will need to:

- Pivot: Move laterally between roles and industries with confidence.

- Layer: Develop multiple deep skills over time, not all at once.

- Connect: Apply insights from one field to another, creating novel value.

So to summarise…

The “I”, “T”, and “M” are not merely metaphors; they represent the evolution of human value in the face of technological change.

Where the pre-industrial worker valued depth, and the industrial worker valued breadth, the future worker must value integration. AI and automation will not replace human capability, they will augment and amplify those who can blend diverse knowledge and skills into innovative, (and ethical) human-centred solutions.

For the young professions to thrive, learning not only how to work hard, but how to evolve effectively is essential. In future articles, I’ll explore practical ways to do this. But for now, here’s something to reflect on: What do you want to be great at? What new opportunities could that open up for your future? And what complementary skills can you build now to give yourself the flexibility to pivot as the world changes?

References

- Epstein, S. R. (1998). Craft guilds, apprenticeship, and technological change in pre-industrial Europe. Journal of Economic History, 53(4), 684-713.

- Mokyr, J. (1990). The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress. Oxford University Press.

- Britannica. (n.d.). Industrial Revolution.

- McKinsey & Company. (2021). T-shaped skills profiles and the human factor.

- IBM Research. (2018). Cultivating T-shaped professionals in the era of digital transformation.